Christina Annunziata, M.D., Ph.D., has dedicated most of her career to studying ovarian cancer with the aim of discovering new treatments for women. She works at the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute. She shares updates on new immunotherapy research and what it could mean for ovarian cancer treatment in the next few years.

Tell us about some of your recent research on ovarian cancer.

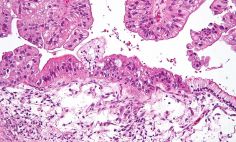

My research focuses on the intraperitoneal environment—or the area inside of the abdominal cavity lining. We are looking at therapies we could use there to treat ovarian cancer. One of the approaches we're taking is looking at the immune system cells in this area. We're also looking at why these immune system cells aren't killing ovarian cancer cells.

What is the role of the immune system in fighting ovarian cancer?

People have two types of immune systems. There's the adaptive immune system, which is what most people think of when they get sick. This immune system is activated by exposure to pathogens. Those are the viruses, bacteria, or other microorganisms that can cause disease. It builds a memory about these threats in order to improve the immune response.

There's also the innate immune system. It works to prevent the spread and movement of foreign pathogens throughout the body. This is the first line of defense against invading pathogens, and it's what we're focusing our research on.

What we've found is that the innate immune system is very important in controlling ovarian cancer. We've also discovered that it can be controlled by ovarian cancer. The cancer is finding ways to escape the innate immune system cells, which are designed to fight it. Our goal is to make the innate immune system work better so that we can better contain ovarian cancer.

How are you doing that?

We are currently performing a clinical trial in which we take the innate immune cells, called monocytes, out of the patient's blood. We use a process called apheresis that separates the plasma from the cells. We stimulate the monocytes, which activates them to kill cancer cells. Once they're activated, we put the cells back inside the abdominal cavity lining.

We're optimistic about this potential treatment, but it's just a starting point for resetting the immune system. It could be used as a platform to build more complex immune therapies, but by itself, it probably won't be a cure for ovarian cancer.

What do you want people to know about ovarian cancer research?

People with ovarian cancer should have hope because researchers are working on new therapies all the time. To speed up the discovery of new and effective treatments, I encourage patients to participate in clinical trials.

It's also important to know that ovarian cancer is not one disease, and the way doctors are treating it is becoming more individualized. For example, we are learning how certain gene mutations and features of different ovarian cancers make them react differently to specific therapies. In the next 5 or 10 years, I think we will be developing therapies that target these specific molecular abnormalities, which we'll be able to identify using diagnostic tests.