Why do patients with fibrous dysplasia/McCune-Albright Syndrome break their bones so easily? Or hit puberty as early as infancy? Or sometimes lose their vision and hearing? Doctors have tried to answer these questions for decades.

Twenty-six years ago, researchers at NIH began piecing it together. Today, clinicians have more effective treatments for this rare disease. And patients have more tools to get the help they need.

What is fibrous dysplasia/McCune-Albright Syndrome?

Fibrous dysplasia (FD) and McCune-Albright Syndrome (MAS) are separate conditions with the same genetic variation. It’s possible to have one condition only, but when they happen together, it’s referred to as FD/MAS. FD is a bone disorder and MAS affects the skin and endocrine system (which regulates hormones in the body).

FD/MAS is a genetic (but not inherited) disease that occurs while the fetus develops in the womb. Some early signs of FD/MAS include large birthmarks across the body and puberty that starts in infancy. The complications can be mild or severe. They include chronic pain, weak or misshapen bones, and a high rate of bone turnover (when bones break down and rebuild). Bone lesions can also grow and press against organs and nerves. This sometimes causes problems with vision, hearing, or breathing.

FD/MAS can also cause hyperthyroidism, which is an overproduction of hormones in the thyroid gland, as well as other endocrine problems.

These conditions can be painful and may lower someone’s quality of life. Treatments include surgery, hormone therapy, or medical device implants.

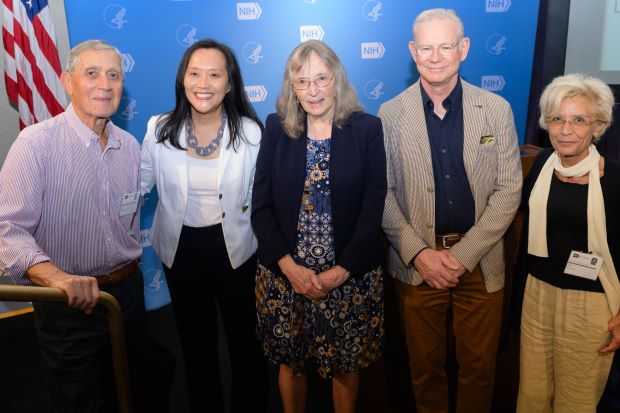

Research by Drs. Allen Spiegel, Janice Lee, Pamela Robey, Michael Collins, and Mara Riminucci (left to right) is helping scientists better understand and treat FD/MAS.

Unlocking the source of FD/MAS

FD/MAS was first recorded in medical journals in 1937, but scientists didn’t know what caused it. In 1991, Allen Spiegel, M.D., of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, led a research group that made a major discovery. They found that a mutation of a specific protein causes the skin issues and hormonal effects of FD/MAS. But what about the skeletal symptoms?

To find out, Dr. Spiegel brought bone samples from patients with FD/MAS to Pamela Robey, Ph.D., at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). Dr. Robey is a biologist who specializes in bone stem cells. She found that the same mutation that causes the skin and hormones problems causes the lesions in bones.

Tracking FD/MAS over the lifespan

In 1998, scientists started a natural history study to learn more about how FD/MAS changes over a person’s life. Dr. Robey and Michael Collins, M.D., an endocrinologist at NIDCR, led this research. More than 300 patients between 1 and 102 years old have already joined the study. Researchers are still recruiting participants. For this study, clinicians examine the whole patient. They record patients’ symptoms, take bone scans and tissue samples, and note how patients respond to treatments.

What we know from the study

The study helped clinicians create more individualized treatment plans for patient care. In 2015, Dr. Collins and Alison Boyce, M.D., a bone disorders researcher at NIDCR, published clinical decision-making guidelines with a flowchart and checklists. Clinicians can put in a patient’s specific symptoms and get back an appropriate treatment plan. Patient advocacy groups have shared the guidelines with people to give to their health care providers. The study also helped doctors better understand when surgery would be helpful or not.

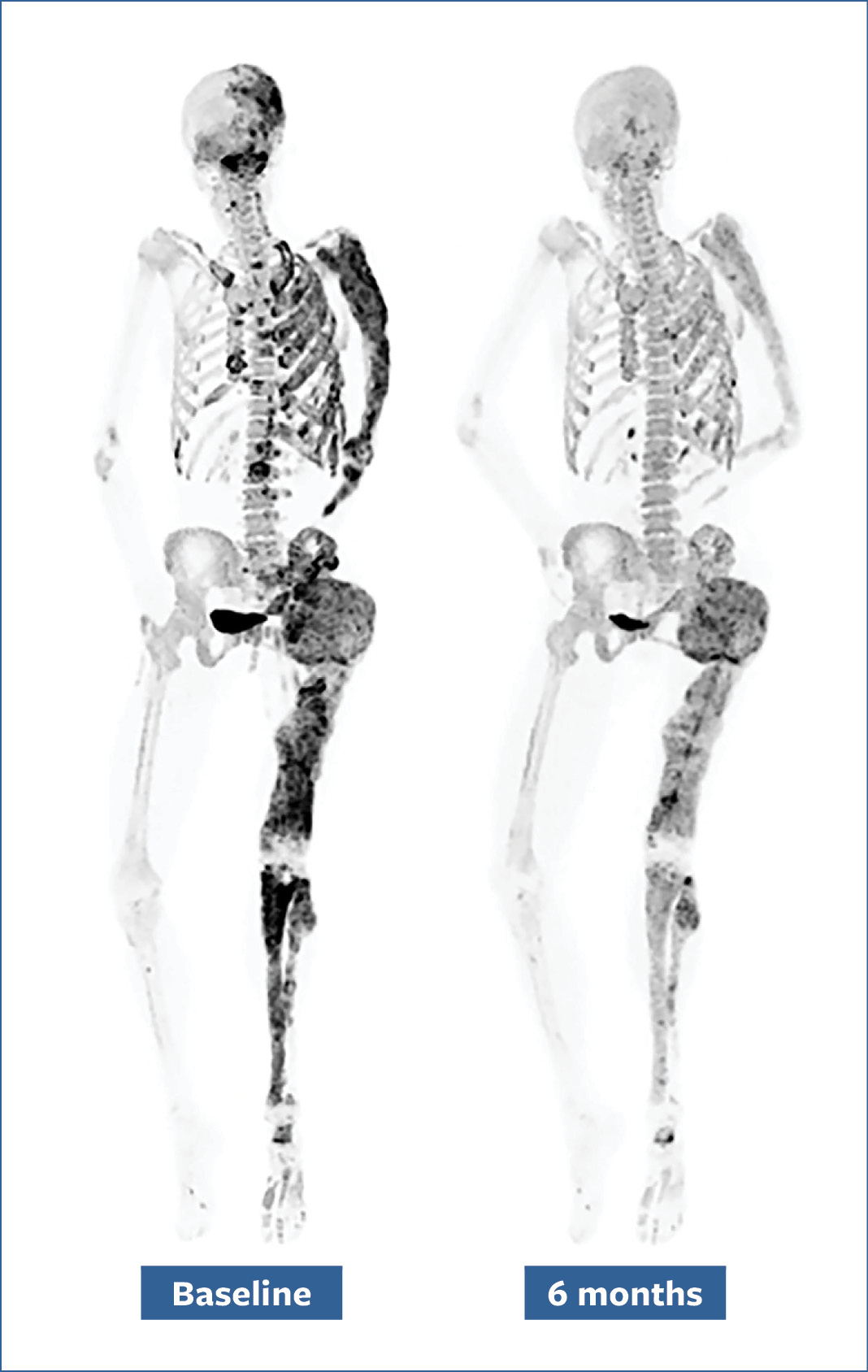

Another discovery revealed that FD cells overproduce RANKL, a protein that increases bone turnover. Bone turnover is necessary and happens throughout a person’s life, but high turnover, as in FD/MAS, can increase the risk of fractures. Researchers found that blocking RANKL could decrease bone turnover in patients. It also prevented new bone lesions in animal studies.

Bone scans of a patient before (left) and after (right) a six-month denosumab treatment show reduced turnover within fibrous dysplasia lesions (dark-colored patches).

What’s still unknown about FD/MAS?

While there are medications approved to treat hormonal symptoms of FD/MAS, there is no way to stop the growth of bone lesions yet. Dr. Boyce’s team is looking into a drug called denosumab—a RANKL blocker normally used for osteoporosis—to see whether it can prevent bone lesions from forming in children with FD/MAS. That study is expected to end in 2026. Another NIH-supported research team in the Netherlands is studying the same drug in adults with FD/MAS.

Dr. Boyce is also leading a study on another drug called burosumab to see whether it can improve blood phosphate levels in patients with FD/MAS. These patients tend to have low blood phosphate levels. Phosphates are minerals that are important for strong bones and teeth. That study is expected to be completed this year.

*This article was adapted from a longer story by NIDCR. Read the original article to learn more about FD/MAS and the researchers who study it.